Honestly, I didn’t really think through the process of my teen son learning to drive and getting his license. Specifically, I completely ignored the fact that someone would have to give him driving lessons, and the reality that someone would be me, his mother.

Driving lessons threw our communication challenges into stark relief. Driving lessons also forced me to lean hard into learning to communicate with my teen son.

As with most oncoming traumas, my brain protected me.

It compartmentalized my son’s driving lessons into a locked safe room behind a barred iron door in the foggy recesses of my mind. It’s not like reality didn’t try to creep in. My husband stated emphatically that he would teach my youngest child (now 13) to drive (someday), but he stated clearly that the responsibility for teaching my son to drive fell solely to me.

And why did my son’s stepfather all but refuse to give him driving lessons?

My son questions authority on issues big and small with the ferocity and vigor of a litigator in training and the dogged, unrelenting persistence of the young.

He debates issues so irrelevant that simply following directions takes less time than challenging them. A fierce advocate for his own point of view, my son frequently flexes his intellectual muscles. In many ways, his pushback, while at the extreme end of the spectrum, is age-appropriate. I both value his pursuit of growth and differentiation and find it irritating and concerning when safety is at stake.

My husband, with his infinite wisdom, foresaw future driving lessons with this kid as an endless stream of questions about and challenges to life-and-death, split-second decisions. As a result, he wisely opted out, leaving me in the passenger seat.

In 2022, driving fatalities reached a 10-year high in Vermont with 74 fatal car crashes. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), teen drivers between the ages of 16 and 19 years old are three times more likely to cause or be involved in a fatal car accident compared to drivers older than 20. All of this evidence backs up my husband’s trepidation.

Giving driving lessons to an authority-averse teenager involves significant risk for all involved.

On the “good news” front, between the reduced need for driving during the pandemic and DMV infection-control protocols, my son didn’t express much interest in driving, highlighted by the coming and going of his 15th birthday without a request to schedule his permit test. Once we figured out the process for him to take his permit test online, he attempted it for the first time without studying (par for the course for this authority-resistant teen.) Predictably, he failed.

For his second attempt, he read the (extremely dense and not well-organized) Vermont Driver’s License Manual

. Yup, you guessed it. He failed again.For attempt number three, he made flashcards for himself and really studied the material to the point of learning it. He passed two weeks before his 16th birthday. Unfortunately for him, this timing proved truly terrible. After five years in graduate school, I was two months away from finishing a spring semester course load of 18 credits and graduating.

I gave him the bad news that driving lessons would have to wait.

In Vermont, the requirements for getting a Junior Driver’s License are appropriately extensive. Teenagers aged 16 or 17 need to hold a learner’s permit for at least one year before becoming eligible to take a road test for their Junior Driver’s License. They must take a “state-approved driver education and training course,” such as those offered at high schools. Additionally, my son needed to complete 30 hours of daytime driving and 10 hours of night driving supervised by an adult in no less than a year. This requirement is where driving lessons with parents, other caregivers, or family members come into play. As promised, after I completed graduate school, my son and I started our driving lessons within the safe confines of our thankfully large and circular neighborhood.

Immediately, the full weight of the difficulty of giving this kid driving lessons bulldozed through my elaborate mental protections and electrocuted my nervous system in full force. You see, I started driving when I was 14 years old. In Montana, where I lived at the time, you can get your permit at 14 and your license at 15. Due to the geographical size of the state compared to its tiny population (similar to Vermont), the licensed driving age is younger than in most states.

How did this impact the provision of driving lessons to my son, you ask?

As it turns out, driving is primarily muscle memory. After driving for over three decades, I lost the ability to isolate or communicate about the physical motions of driving, and the exact details of how to drive, to my teenage son. Learning to communicate with my teen took a backseat to learning how to teach driving.

Having my muscle memory disconnected from language meant re-learning how to talk about and explain the mechanisms of driving while teaching my son to drive. It felt like building a plane while flying it.

To complicate matters, our communication has never been great. Our brains process information about the world differently. These communication barriers frequently lead to misunderstandings, hurt feelings, and stubbornness on both our parts. In most situations, I adapt by avoiding conflict unless the issue involves safety, which meant our communication skills remained woefully underdeveloped when it came time for driving lessons.

For a couple of months, I confined our driving lessons to the safe and often empty roads of our neighborhood, mostly due to my inability to communicate directions to him verbally.

For example, he asked, “Mom, how much pressure do I put on the brake when I’m slowing into a turn?” To respond, I had to change places with him, pay attention to how and when my foot found and pressed the brake going into a turn, put language to that task, change places with him, and talk him through it.

Even when I possessed the language to describe a maneuver, the words or phrases I used often failed to make sense to him. When teaching him to back into our driveway, I instructed him to “swing out toward the mailboxes across the street.” After his multiple attempts without a hint of “swinging out,” he informed me he had no idea what I meant by that.

It felt like the cooking enchiladas scene between the mother and son in Schitt’s Creek. The mother keeps telling her son to “fold in the cheese,” and he becomes increasingly frustrated by this instruction that he cannot understand and she cannot fathom a different way to express this basic task.

During driving lessons with my son, I constantly felt like I was telling him to “just fold it in!” while he gave me the side eye and responded heatedly, “I don’t know what that means!”

Tension grew between us as he pushed to leave the neighborhood and practice driving in the larger world on busier streets, while I avoided this eventuality, unable to fathom communicating with him effectively in higher stakes situations.

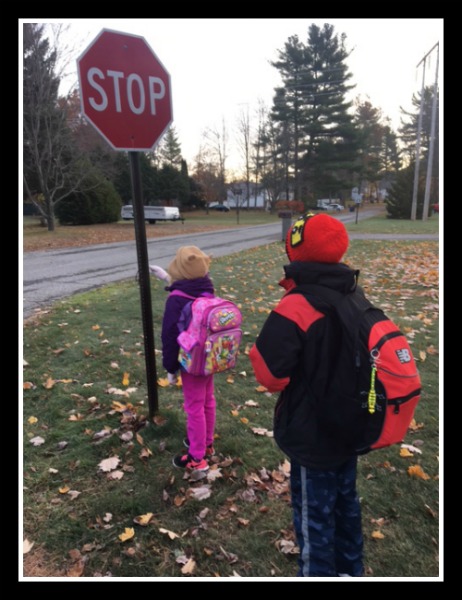

Luckily, around this time, he visited his biological father out of state. Since my ex-husband’s communication style and way of thinking more closely match my son’s, their driving lessons progressed far beyond what I felt capable of providing, including highway and night driving. Upon his return to Vermont, my son and I made several bolder driving forays, including an extended highway trip to visit Dartmouth. Our communications improved further, though we still encountered a few close calls, like him not seeing a stop sign until I yelled “STOP!!!”

Eventually, he enrolled in Driver’s Education at his high school, and an expert took over his driving lessons for a semester. This expert possessed the ability to put language to muscle memory and give concrete reasons for rules of the road that my son needed to know and that I lacked the patience or knowledge to provide.

When he stated, “Headlights hurt my eyes. Why can’t I wear sunglasses at night?” I responded to ask his Driver’s Ed teacher because I knew any explanation I gave without being able to cite the exact statute would be dismissed. My son accepted his teacher’s knowledgeable answer, “It’s not necessarily illegal, but it’s definitely frowned upon.”

As we continued our driving lessons to complete my son’s required 30 daytime and 10 nighttime supervised driving hours before scheduling his road test, our communications, his compliance with directions, and the safety of his driving got better and better. I really was learning to communicate with my teen son! I even let him drive me through a snowstorm during one of our practice sessions.

I am proud to say he successfully passed his road test, earning his Junior Driver’s License. He demonstrated the extent to which we overcame our communication barriers by predicting my behavior for his road test administrator: “Watch. My mom is going to scream and jump up and down when I tell her I passed.” Yup, I did. Following his accomplishment, he took a big step forward in assuming responsibility for transporting himself to and from school, his part-time job, and his extracurricular and social activities.

As a bonus, learning to communicate with my teen son through hard-won driving lessons, translated to communication improvements in other areas of our parent-teenager relationship. I now feel more capable of supporting him in his emerging adulthood, and he confides in me more, recognizing the trust we built on the road together.

And the best part? I’m done giving driving lessons. In two years, my husband gets to take that wheel with our youngest child, and I can relax at home. Although, after improving communications with my son through driving lessons, I’m wondering what I might miss if I give up this experience with my youngest kid…

Have you taught a teenage child to drive yet? How was your experience? Did you find new and better ways to communicate?

Pin this post and be sure to follow Vermont Mom on Pinterest!

Vermont Mom Insiders get exclusive content that you do not want to miss, so sign up today!